I was just leaving the private view of an exhibition which included some work by my erstwhile musical collaborator, Ken Ritchie, when I bumped into another friend, Jennifer Thomas. It is not unusual to bump into friends in the Thoroughfare in Halesworth.

Jennifer was recently widowed. Her husband Edward, a descendant of the poet Edward Thomas, was a gentle man, who took on the job of pouring glasses of wine for visitors to the Halesworth Gallery’s

exhibition openings. He often wore a cravat and poured carefully. Jennifer was, of course, grieving but was certainly not planning to sit on her hands in God’s waiting room.

She told me that she would soon be going to Tigray to do some art teaching in a mission school, run by the daughter of one of her friends. She wanted my ideas about what she might do with a classroom of Tigrayan teenagers. We arranged for her to come round to my studio the following week, when I was able to make several suggestions for art activities. She was very grateful and a bit relieved, I think, as she has never taught art before, although she has painted many pictures.

Around about this time, Meles Zenawi, who had been prime minister of Ethiopia since 1995, passed away. A couple of nights after hearing this news, I watched ‘Marley’, the enjoyable, if rather lengthy, film about Bob Marley’s life. As a result of of these three events - Jennifer, Meles, Bob - I began to think again about the work I had done in Ethiopia...

In 1991, I was doing graphics commissions for various clients. Jon Marsh of ‘The Beloved’ used my

images for most of his record covers. I designed a brochure for the Urban Health Programme of the

London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, the image coming from that bit of my brain reserved for the slums of Mumbai, where I had worked several times during the ‘80s. At the other extreme, in terms of housing, I also worked on illustrations for an 8-page leaflet about the National Trust’s Country Houses. A cover for Practical Action’s journal ‘Appropriate Technology’, a poster for the Coin Street Festival, an album cover for Colombian musician Lisandro Meza, and so on.

REST

In the same year, our group Health Images had been in touch with an organisation, based in London, with the slightly misleading acronym REST. This was the Relief Society for Tigray. In the late 1980s there had been great opposition and numerous insurrections against the Ethiopian government, known as the ‘Derg’, headed by Mengistu Haile Mariam and supported by the Soviet Union. Mengistu had been one of the main players in the overthrowing of Haile Selassie, the last emperor. In the late 1970s the Derg committed horrendous atrocities on tens of thousands of Ethiopian citizens, during a period known as the ‘Red Terror’. In 1989 the Tigrayan Peoples Liberation Front (TPLF) joined with other northern opposition groups to form the Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF), in order to fight against the Derg.

In 1991, a colleague at REST sent me a booklet entitled ‘Documents from the First National Congress of the Ethiopian Peoples Revolutionary Democratic Front’. This was a strange and seemingly naive publication, a sort of utopian manifesto for the future of Ethiopia. Its sections were called things like ‘On the Multiplicity of Political Parties’; ‘On a Revolutionary Democratic Economic System’ and ‘On the Ethiopian Peoples Democratic Revolutionary Front Transitional Program’. Phew! Hard going Panglossian fantasies. At the beginning of the section on ‘Agriculture’, it read, amazingly, “...all land shall be owned by the state; the state will provide land to all those who want to use it, free and on the basis of equality; land will not be bought or sold or be used as collateral”. Wonderful idealism.

The hatred of the Derg had led to all-out war in the north, between the Tigrayans and Eritreans on one side and the Derg army on the other. Some of the Tigrayan fighters would later attend our workshop at Wad Medani in Sudan. 1989 was the year that the Berlin Wall came down. The Soviet Union reduced its aid to Mengistu and stopped it completely in 1990. In May 1991 the EPRDF forces advanced on Addis Abeba and soon Mengistu had fled into exile in Zimbabwe. In 2008 the Ethiopian Supreme Court sentenced Mengistu, in absentia, to death. Wikipedia says that some commentators estimate that he was responsible for more than 2 million deaths.

WAD MEDANI, SUDAN, 1991

Following further meetings with REST, we managed to come up with a plan for collaboration and in June 1991, just after the EPRDF had taken Addis, two Health Images colleagues, Petra Rohr-Rouendaal and Sammy Samkin, arrived, hot and dusty, at the Wad Medani Rehabilitation Centre in Sudan to run a workshop funded by REST and Christian Aid. As usual, the aim was to teach participants to make and use graphics for health education. This was to be a very tough workshop. Firstly, the Rehabilitation Centre for wounded Tigrayan fighters, was on the south eastern edge of the Sahara Desert, in Gezira province - the temperature there reached 52 centigrade during the time of the workshop. Although close to the Blue Nile, just a couple of hours drive south from Khartoum, the Rehabilitation Centre was in the desert, next to a very large refugee camp of tents and plastic sheets. Water was in short supply and sanitation arrangements were, at best, basic. The walls of the Centre were made from barrels which had been flattened out and fixed together to make reasonable walls - security was very tight there.

All eight of the workshop participants, seven men and one woman, were ex-fighters who had survived the civil war but been badly injured in battle. They were severely physically handicapped - five were paraplegic, as a result of spinal injuries, and suffered some degree of paralysis. One participant had two artificial legs, not too comfortable in that sort of heat. Another man had had both arms amputated at the elbow, while the eighth participant had no hands, half an arm, both feet and half of one leg missing. Missing in action. The participants were Enquay Gebreselassie, Gebrehowria Berhane, Gebremeskel Devesay, Hailu Haymanot, Mahmud Mahabed Saleh, Shishay Tekia, Desta Beyene and Hadas Gebrehiwet, the only female.

One of the aims of this workshop was, of course, to help in the rehabilitation process of these injured ex-fighters. After their strenuous efforts in difficult circumstances, Petra and Sammy wrote an understated report of the training. Work regularly began at 5.00 am, to avoid the heat of the day - in line with the academic classes being taught at the Centre.

From the report - “The squegee pullers managed extremely well, despite their physical handicaps. The major problem that emerged was that none of the students were physically able to take out the print, walk across the room and hang it up to dry”. Reading this makes me think of John Mafanguelo’s linocut of a blind man carrying on his shoulders a “creep”(cripple) man. Co-operation must be more than usually important for disabled people.

DEBRE ZEIT, ETHIOPIA, 1994

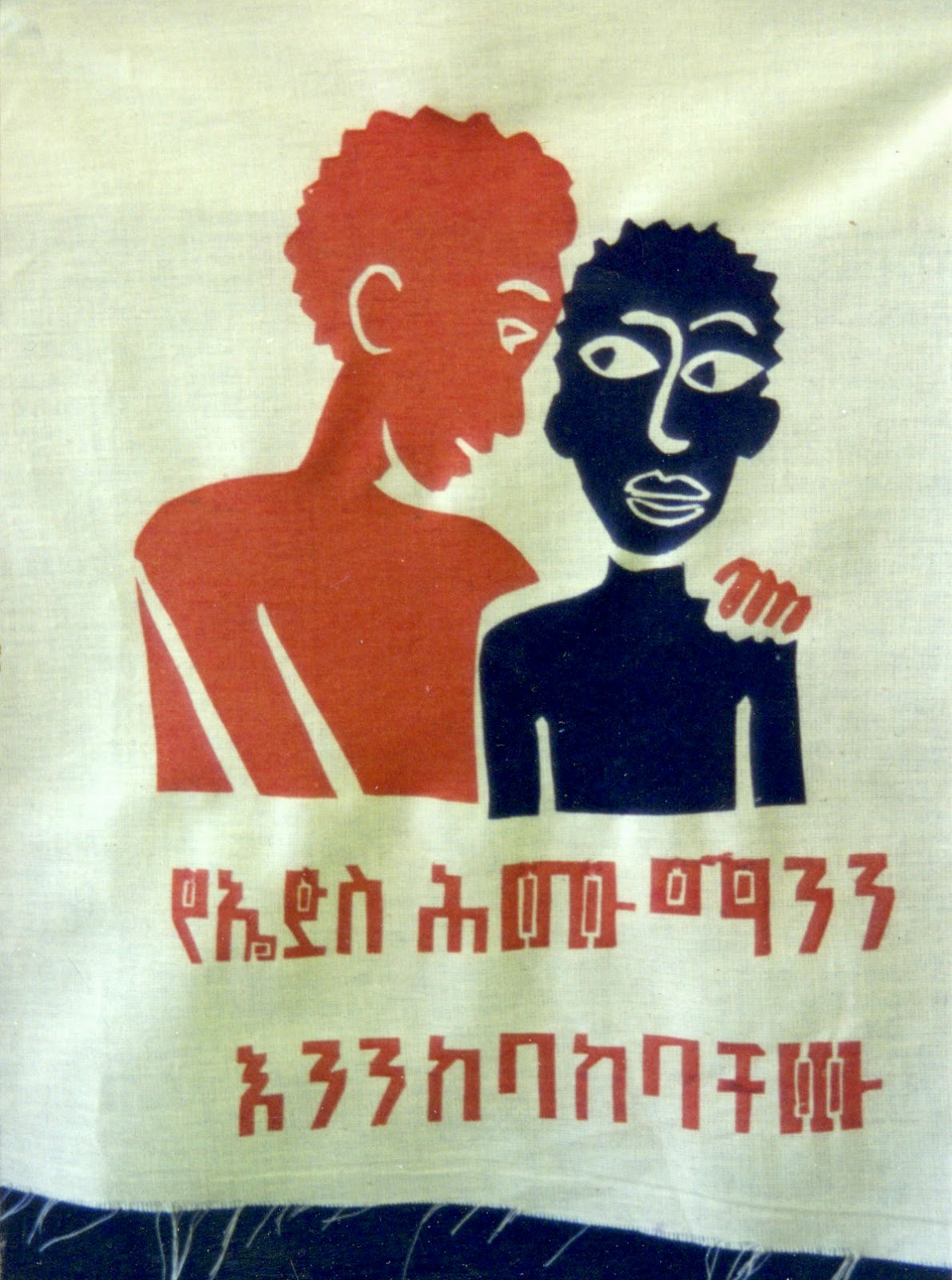

In February 1994, Yezichalam Kassa, of Oxfam, Ethiopia and Petra Rohr-Rouendaal, of Health Images, made a two week field trip all around Ethiopia to assess the need for visual materials which could be used for HIV/AIDS education. On the field trip, Yezich and Petra met a wide variety of people, from bar-ladies and truck drivers, to health workers, educators and AIDS counsellors.

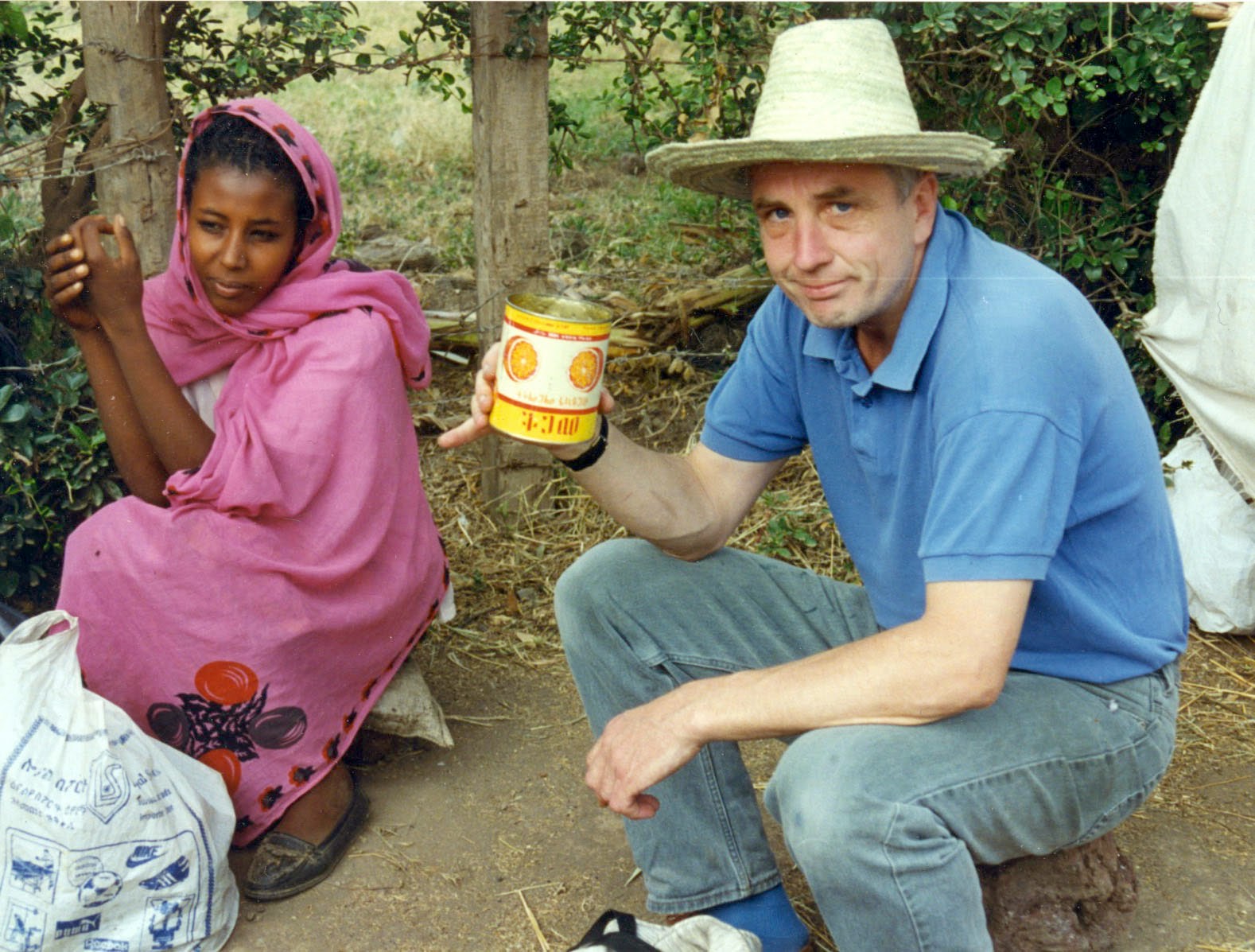

Following on from this, Oxfam decided that training about making and using pictorial materials would be useful for HIV/AIDS counsellors from around the country. Thus, early in November of that year, I found myself in Debre Zeit with Petra, Liz Brown and Yezich, together with a group of eighteen AIDS counsellors from different parts of Ethiopia.

At that time I had, as usual, been working on various graphics commissions for arts groups in the UK. These included posters for Pop-Up Theatre’s productions “Seasons” and “Big Voice”, a Christmas card design for the World Land Trust, an edition of screenprinted posters for the first year of the Suffolk Open Studios project (this is still going and they still use the logo I designed for them at that time!), a poster for the London Festival Orchestra’s production of “Animal Blockbusters” at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, some designs for the Centre for International Health Studies at Strathclyde University, and two 6-page A5 leaflets for the National Trust about “The National Trust and Nature Conservation” and “The National Trust and the Coastline”.

From my diary - “Good overnight flight on Ethiopian Airlines. Driving into Addis I was struck by the amount of corrugated iron - roofs, walls, fences, etc. Also saw a small man wearing a large, old pith helmet - a faded brown colour. It would be nice to know its history - no doubt it could tell some interesting stories. A sign in front of a small corrugated iron hut - ‘East Africa Break Lining Work’”.

The workshop was opened by Chris Mason, Oxfam’s Country Representative in Ethiopia, on November 7. One of the liveliest participants was a wonderful man called Jirane Mamo, who kept us going at times with his jokes and stories. At the start of proceedings, he addressed the group, saying

“When we were young children, sometimes we would play games before going to school in the morning. We were playing and dreaming, forgetting that it was a day for school. Then we heard the school bell ring. It made us aware that we had to stop our games and go to our lessons. In our work with visual aids, we are ringing the bell also”.

Next, Jirane told us that “In our area, Arba Minch, there are lakes with many crocodiles. If you swim there, you cannot see the crocodile but it is very dangerous. It can kill you. This is like the HIV virus. You cannot see it but it is there and it, too, can kill you.”

In Jirane’s terms, this workshop was about ways of ringing the bell to warn of the crocodile. Participants soon got to work on their various images.

Endale Tadesse decided to make a picture about the dangers of cutting the uvula with unclean instruments. The uvula is the little piece of flesh that hangs down at the back of your mouth, in your throat. In some parts of Ethiopia, this is cut off in young children, often in a ritualistic way. The rationale for this practise is that it helps prevent throat and respiratory infections - a dubious claim.

Kadiga Beshit, one of the participants from the Omo region in southern Ethiopia, focussed on the practise of circumcision of young boys. Again, the problem is that HIV can be spread by the knives used, if they are not properly sterilised.

Tadele Kadoug made an image about tribal scarring, which showed a person undergoing this procedure with the use of a dirty razorblade. Tadele came from Mekelle in Tigray, and told us about the great monument there to the TPLF fighters who lost their lives during the war with the Derg.

Jirane’s first input was to do a drawing of a naked couple making love on the floor of the forest - it

provoked much laughter but was felt to be too explicit for widespread use!

Ketema Bekele, also from South Omo, designed a discussion starter showing a group of young Hamar people at an open-air dance ceremony. It included images of couples going off into the forest to have sex. Ketema pointed out that sexual behaviour among the Hamar is quite promiscuous and that Hamar men are very reluctant to marry girls who are virgins.

Dida Wario, from the Borana region of southern Ethiopia, designed a flannelboard about polygamy and extra-marital sex among the Borana tribe.

During the week I had had to go back to Addis with Yezich to find out more from the suppliers about the printing inks we had at the workshop. I discovered that to use the inks, four different chemicals had to be mixed together, in specific proportions! We also had to buy a saw, some cloth, a drill bit, plastic buckets for mixing papier mache etc. I always find it interesting going round these types of shops in foreign countries, making enquiries and purchasing things at the pace of the place, getting handwritten receipts. We saw quite a lot of the city that day and I was again struck by the large number of beggars and disabled people.

That day, one of the participants, a somewhat crotchety man by the name of Milkias, has started to design a board game about HIV/AIDS. He was very enthusiastic about it, not to say obsessive. When I got back to the workshop, Petra told me she’d had quite a difficult afternoon, as Milkias had ear-holed her for most of the session. I sat down next to Milkias at supper, at 7.15, and got up at 8.20, during which time Milkias talked non-stop about the game he was planning. He had hardly started to design it, yet he was already telling me that he was going to try to get some famous actors and actresses to play the game on TV here. I thought this was a silly idea, as only a tiny proportion of people had TV sets. He predicted that when we next visit Ethiopia, all the kids on the streets of Addis will be playing this hitherto conceptual game! He’s also planning to print the game on the back of t-shirts - it will be called ‘The Game of Life’.

The food at the workshop has been good - lots of saladdy stuff and every day large quantities of diced

beetroot with chopped chilli and raw onion. Injeera, of course, and various types of wat...Most evenings we had a couple of cans of ‘tulla’, the local home-made beer, sold by a woman who lived near the training centre.

On the Friday night some of us went to a bar in the town to sample the other typical Ethiopian drink ‘tej’, made using honey and served in characteristic little bottles with long necks. Great at the time but not so good waking up in the middle of the night with a memorably dry mouth. In my diary I wrote that tej was “Nothing to write home about” and I couldn’t remember the title of the Alan Bennett book I was reading with a dry mouth , so looked it up. It was, of course, ‘Writing Home’. Strange. Like my room number 121 echoing the slogan used by the Catholic participants for Aids education - ‘One to One’.

There were bottles of beer, too - one of them called ‘Saint George’, with Georgiu and the dragon on its label. We had a good chat - one of the participants said he’d take us to his home town of Nazareth. All very Christian, lots of crosses everywhere. Another participant was called Solomon, a large, urbane man and good drinking partner. Many of the old Ethiopian paintings show King Solomon in bed with the Queen of Sheba (apparently, Sheba means ‘south’ in one of the languages), about to, or just having, conceived Menelik 1, the first emperor. Some of that old artwork resembles comic strips. We discussed the use of comic strips in HIV/AIDS education at the workshop and one of the participants commented that comic strips were a Western invention, so I reminded him that it was an ancient style in Ethiopian culture.

On Saturday morning, a group of us went for a walk and a boat-ride on the lake next to the

Galilee Mission, just outside Debre Zeit. Jirane and Kadiga made us, and themselves, laugh a lot by

demonstrating some hilarious traditional dancing from North Omo. Jirane also treated us to his

impersonation of a bullfrog.

In the afternoon, we went to the market in Debre Zeit. By this time, I was becoming aware that the

political situation here is quite tense. I wrote in my notebook at the time - “It’s all very complicated but there seems to be widespread dissatisfaction with the EPRDF interim government. The West seems to be supporting the government and foreigners like us are not popular, as we found out rather dramatically in Debre Zeit market today. In brief, one of the participants was hit by a man because we were taking photographs. We were sort of driven out of the market by a crowd. It was a bit scarey, but nothing much happened.”

“There are quite a few soldiers around, with guns. There are so many weapons here after the civil war. We are told that there could be a lot of violence in the future”. As luck would have it, things didn’t turn out as bad as some people had feared.

That day, I remember showing a British £10 note to Dida, one of the participants from the Borana region. He had never been to Addis or Debre Zeyt before. He studied Queen Elizabeth’s face on the note very carefully and then turned to me and asked “This man for work, what thing he do?”.

On Sunday, we all went to a place called Sodere for a workshop outing. Sodere is a resort for affluent

Ethiopians. I wrote in my notebook -

“The journey there was pleasant, lovely countryside in the huge African landscape. It’s harvest time and the fields looked golden with small sheaves of teff and little haystacks. Threshing was done by a team of oxen walking round in circles on a pile of teff”. (Teff is a cereal grass from which injera, the staple of the Ethiopian diet, is made). “Small boys on the roadside selling neat round bundles of short sticks of sugarcane, others with huge bunches of bananas held aloft above their heads. And mountains in the background, Rift Valley scenery. You could see for miles, all the way round the horizon.”

As we arrived at Sodere, which consists mostly of a large swimming pool and a nasty looking hotel built a few years ago during the Mengistu era, some young boys came up to our vehicle carrying young crocodiles, which they wanted us to buy as souvenirs.

Their specimens looked like they had been rather inexpertly stuffed. I assume they were young Nile crocodiles whose lives had been cut short in the hope of alleviating the boys’ poverty. Conservation and humans - a sad and complex tale. Petra, Liz and I hated the place while the participants thought it was great. We did see a few interesting things there - the fast-flowing Awash river (appropriate name for a fast-flowing river!), lots of baboons and several smaller monkeys with bright blue testicles. We spent most of the day relaxing, drinking beer and chewing the ubiquitous ‘chat’, a plant with mildly narcotic effects, which Ethiopians have, historically, been using since before they drank coffee. The participants had bought several carrier bags full of the stuff before we left Debre Zeit - a weekend treat. Many Ethiopians actually chew chat daily, as do people in other countries in the region. Apparently in Yemen something like 40% of the country’s water supply is used to irrigate the chat crop.

Back at the workshop, we had reached the point where participants needed to go out into the community to get some feedback from local people. Kadiga was a bit disappointed when someone said, of her design, “The boy is floating in the air”. Almaz was told that the people on her image “look like doll, not human being”. Ketema, who showed his design about tribal scarring, was told “this picture should also be made appropriate for the Afar people”. Endale’s image of cutting the uvula prompted various comments, including “Mother should turn her face away, as normally she would not be able to look” and “Children would normally be in traditional dress”. One respondent made the withering suggestion that “the faces should be more human-like”.

One day, I got chance to have another chat with Dida. He had been to Addis for the first time in his life and I was interested to know what he made of it. “There are many thieves there”, he said, “I do not like it much”. We got onto talking about football - at one point Dida told me, rather bluntly, “Your time for running is past. You are old. Now is my time for running. I am young. I will run until I am thirty years old.” Thanks, Dida.

At the end of the workshop, some of the participants put on a puppet show about HIV/AIDS using the papier mache puppets they had themselves made. Some of them had been made using inflated condoms, of which we had a plentiful supply, as one of the participants, Teshome, was employed by the HIWOT Trust, whose work includes distributing condoms in large numbers.

It was fun. The bags under my eyes were noticeably bigger at the end than at the start of our work and Petra was similarly exhausted - although she was going straight on to northern Kenya to do some work with a group of Samburu people. As usual, I was looking forward to getting home while feeling a little sad about leaving these people who I’d got close to for a short time. I had eaten far too much injera wat, not forgetting beetroot, in a country best known in the West for its famines. I would miss the night sounds, too - crickets chirping, owls hooting, wild dogs barking in the distance. And no more cleaning silkscreens with Omo powder with a man from South Omo.

ADDIS ABABA, ETHIOPIA, 1999

In March 1999, Liz Brown and I did a workshop with a group of street kids in Addis. On this occasion, we collaborated with a small organisation called ‘The Ethiopian Gemini Trust’, whose main aim, according to their information leaflet, was to “save and support twins born to needy families in Addis Ababa”.

Earlier in that year, I had done a few graphics jobs. These included an A2 poster for the World Land Trust about the conservation of what was left of Brazil’s Atlantic Rainforest. Their work focussed on the Guapi Acu project area, inland from Rio de Janiero, which is home for hundreds of species of plants and animals that are found nowhere else on the planet. These included jaguar, oncilla (a tiny cat) and the very rare woolly spider monkeys, as well as a range of interestingly-named birds - saw-billed hermits,violet-capped woodnymphs, white-collared foliage-gleaners, star-throated antwrens, velvety black-tyrants, brassy-breasted tanagers and green-chinned euphonia. Then a leaflet to announce the launch of the Asian Music Circuit’s first website. It was fairly early days of Photoshop for me, so most of the images have been played around with - solarised, inverted, blurred, curved, etc. - because you can. I managed to include a nice image of a Bhil musician on the back (Bhils are tribal people from Maharashtra and Gujerat), taken from one of my all-time favourite books, “The Earthen Drum” by Pupul Jayakar. The other AMC leaflet was a posterised image of Ronu Majumdar, a wonderful bansuri (bamboo flute) player who was coming to the UK to do a concert tour. I was lucky enough to see him and table maestro Abhijit Bannerjee perform at the Athenaum in Bury St. Edmunds in May of that year. The other commission I worked on was a large 25th anniversary poster for the Intermediate Technology Development Group, now called Practical Action. It showed a vaguely African-looking woman carrying a pile of books published by IT Publications, with titles like ‘Small Enterprise Development’, ‘Appropriate Technology’, ‘Engineering in Emergencies’, ‘Whose Reality Counts?’, ‘How to Make Carpentry Tools’, ‘Training in Food Processing’ and ‘Small Scale Irrigation’. In the background were small illustrations of the sort of technology that ITDG was promoting.

The Ethiopian Gemini Trust was founded in 1983 by Dr. Carmela Abate, a paediatrician then working at Addis Ababa’s main teaching hospital. The birth of twins in Ethiopia is not always a joyous event. The information leaflet says that Ethiopia has “proportionally twice as many twin births as in Europe”. Apparently, the highest rate of twinning,globally, is found among the Yoruba people of south-western Nigeria, where there are something like 45-50 sets of twins born per 1000 live births - that is 90-100 babies per thousand! This might be because the Yoruba eat a particular type of yam that contains a high level of a phytoestrogen, which can stimulate the ovaries to release an egg from each side. In the UK, the twinning rate is about 16 per 1000 or 32 babies. Other hot-spots are the town of Igbo-Ora, also in south-western Nigeria; the village of Kodinhi in Kerala, India; and the settlement of Mohammadpur Umri in Uttar Pradesh, India. Another place with an amazingly high twinning rate (around 10%!) is the town of Candido Godoi in southern Brazil. People there are largely of Polish or German stock, whose ancestors mostly came from a particular region of western Germany called Hunsruck, where twinning is common. The very high rate at Candido Godoi may be explained by a degree of genetic isolation and inbreeding as described by the genetic phenomenon known as the ‘Founder Principle’.

Twins born into the slums of Addis face a real struggle to survive - one in three die before their first

birthday. Two mouths to feed instead of one. Many mothers are malnourished and can’t provide breast milk for two, so they turn to bottle feeding with all its attendant health risks. Gemini has provided support and emergency food aid to two thousand poor families and implemented an on-site feeding programme, as well as providing basic primary health care for all its families. They have run a day-care centre and supported large numbers of children in their desire to go to school. In addition to these activities, Gemini has run a youth club which is attended by street children and other disadvantaged kids, where they have the opportunity of receiving psychological counselling and getting involved in the creative arts. Two of their best known projects are the ‘Adugna Community Dance Theatre’ which trains young people in traditional and contemporary dance, and ‘Gem TV’, a community video initiative.

We arrived at the Atlas Hotel in Addis around 10 a.m. after an overnight flight. It was a pleasant little place, not without its idiosyncracies. We were given rooms on the top floor and it struck me as slightly ironic that, while the rain sounded very loud on the tin roof of the hotel, I was unable to get any water out of the taps or the shower, to have a wash after the flight. In the afternoon a young man called Mekdem came to take us to the National Museum. We had briefly met Mekdem in London and were pleased that he spoke good English, as, in true British fashion, we had not learnt any Amharic. We were thinking of taking the street kids on a sketching trip to the museum. It was a spacious and rather empty museum containing several very interesting artefacts, the most famous of which was the plaster cast of the skeleton of the early hominid named Lucy. The real Lucy is preserved in a private part of the museum. Lucy was found in a village called Hadar, in the eastern Ethiopian region of Afar, near the valley of the long Awash River, in 1974, by a team of anthropologists which included Mary Leakey. Apparently the skeleton was called Lucy after the Beatles’ song ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’, which one of the team played regularly on a tape player in their camp. Lucy was less than 4 feet tall but, importantly, walked upright! We thought the workshop participants would like the museum.

That evening we had a great meal - “...went to a nice traditional, hut-style restaurant and had a delicious vegetarian meal served on a big round tray. A huge round slab of injera formed a sort of plate, on which were lots of little mounds of beetroot and apple salad, lettuce and tomato, mashed-up beans, mashed chickpeas, a mound of sliced peppers, carrot and something unidentifiable, and two fresh green chillies.” I ate loads. The injera was very good, fresh and airy. You tear bits off and pick up the other ingredients with it, so, in a way, you gradually destroy your plate by eating it! This was accompanied by a couple of bottles of Bedele beer.

The following day was Sunday, so we took advantage of this bit of free time before the workshop began. We went to visit a rock-hewn church, Lalibela-style, called Washa Mikael, just on the outskirts of Addis and surprisingly rural. Under great big wide skies, we walked up a big hill, accompanied by three little boys, through an aromatic plantation of eucalyptus trees, from which women and girls emerged carrying massive bundles of sticks on their backs. We met a man at the church who took us to his hut to meet his wife, mother and kids. We had a cup of coffee made from beans roasted on the spot - incidentally, coffee beans were possibly first grown in Ethiopia. I’m not sure if coffee is the main export of Ethiopia - if not, it’s animal skins.

It had been a really good climb for the exercise, the air so fresh, breezy but not too hot, in the wide, wide landscape. We walked on, now accompanied by our new friend, further up onto a plateau from which we had a great 360 degree view.

From the small settlement of thatched huts on the plateau, a few toddlers emerged to greet us before we passed down to a very nice, very rustic village bar.

It was actually a lodge on the drovers’ trail, people from further north, Wallo or Gojam, en route with their animals to the market in Addis. Outside the bar were pens for livestock, empty at the time, but one could imagine the liveliness of a night when the drovers were staying, the tej flowing, laughing and joking rough country men. They always stationed one man outside the party, armed with a shotgun to deter rustlers.

We went into the bar, where a few locals were having a Sunday lunchtime drink. Their eyes popped slightly out of their sockets when they saw us but soon relaxed back into their customary positions. One old man, whose eyes each looked in a different direction, was wearing an ancient military cap and sported a couple of medals pinned to his jacket. He told us he had served in Haile Selassie’s army, (a dubious distinction, in my view) and had been to Korea and to the Congo at the time of independence there. The other men were very friendly, shoeless pastoralists. It was a pleasant interlude, the place being so un-urban, yet so close to the city.

We were due to start work on the following day, so in the morning we went to the Gemini Trust centre, a busy, active place with offices and clinics made from shipping containers above which corrugated iron roofs had been constructed. They do community health work in the slums, family planning stuff, a supplementary feeding clinic for baby twins, and income generation activities for the mothers of twins (as if they haven’t got enough on their plates!). These included marketing spices - that morning they were working on garlic, peeling it, washing it, pounding it with pestles and mortars, drying it and eventually turning it into garlic powder to be sold in grocery shops here, as well as going for export. Here, too, a father of twins and one of his elder sons make silver jewellery - crosses, rings, filigree work. They buy Maria Theresa dollars, which are pure silver, melt them down and turn them into jewellery. (Maria Theresa dollars were first minted around 1750 in Austria but had reached Ethiopia within a couple of decades. They seemed, for some reason, to have been particularly popular in Ethiopia - some say that, of the 245 million minted up to 1930, nearly 50 million of them ended up in Ethiopia). Another man, a father of triplets, was working at a weaving loom. All around were twin babies and small children and a few triplets - it was very strange, like seeing double.

We then went on to Kazanchis, an old, interesting part of Addis, currently being knocked down and

‘modernised’, which is where Gemini do their work with street kids and other young people from poor families. Most of these kids come from families with 6-10 children, many of their families being so poor that they usually only have one meal a day, sometimes none. Imagine cooking for 9 or 10 children, with no running water! In fact, the degree of poverty is really extreme, just little shacks with one or two rooms, many people begging and really pleased if you give them 10 cents (15p).

We started the workshop with an enthusiastic group of young people who were keen, at first, to practise and learn about drawing. The work is being done in another shipping container, the walls of which have been lined with plywood, with a couple of windows cut in one side. It was usually quite cramped and warmish but always with a good atmosphere from the group. To give you an idea of some Ethiopian names, the young people, all between 14 and 18 years old, were Fatuma Naru, Mohamed Kulfa, Tesfaleu Tadese, Wondimu Yimer, Genet Kussa, Betelhiem Tafesa, Mesfein Gezehagn, Etagenh Shiferan, Zeritu Tesfaye, Meseret Kebede, Aynalem Ensa, Genet Gebre, Beletu Negusie, Misganour Abebe, Habte Idosa, Ermias Tesfaye, Abel Kebede, Fikadu Tesema, Meaza Michael, Tarikua Yimer, Genet Mogas and Munige Shiferan. It was a bit difficult for the first couple of days to remember everyone’s name but we did succeed in getting a handle on these after a while.

As usual, the content of the course was determined largely by the expectations of participants. Here, these mainly concerned their desire to improve their drawing skills. Other ideas related to visualising aspects of life on the streets, as most of the kids were school dropouts who had spent time as street-

workers or street-children. Several of the participants were shoeless, many had old torn clothing, some were a bit more affluent and nicely dressed in clean clothes, most had runny noses and varying numbers of pimples. They were all great to work with and we had lots of laughs as they got on with their drawings. We had taken several resource images for them to look at, including some showing traditional Ethiopian art styles. They didn’t recognise the latter as being Ethiopian. After some drawing exercises, participants were asked to draw a picture of where they lived and who they lived with. This was intended as a way of beginning to focus on the participants themselves, and on their own lives and experiences.

The work continued at a slow pace for the next few days but participants were making great progress with their drawings. Our evenings were mostly spent at a little bar/restaurant near the hotel, watching the street life go by. Nights at the Atlas Hotel were, for me, mostly spent trying to get some sleep despite the endless dog howls that sparked each other off all around us and subsided only around dawn, to be replaced by the tinny voice of an Ethiopian Orthodox priest intoning his early morning gibberish.

I had forgotten about the altitude of Addis - 2,300 metres (nearly 8,000 feet) - as we went about our

business. The sun hadn’t felt very strong but, after a short time, I noticed that my forehead and nose had gone quite red...a pleasant climate, however, in spite of the ubiquitous diesel fumes. I had also borrowed a guitar, so things were going OK. One evening, Liz was unwell, so went to bed at 6 o’clock. I took the opportunity to do a bit of work designing the poster for that year’s Lichfield Festival, the deadline for whichwas vaguely looming. It was a bit incongruous but very enjoyable to be doing my own graphics again, rather than helping others do theirs. Lichfield Festival, thinking about it from the Atlas Hotel, seemed extremely English, with music in the cathedral, including a performance of Elgar’s ‘Enigma Variations’, Bill Oddie talking about birds, string quartets and guided country walks.

There had been rumbling talk of war while we were in Addis - from my notes - ‘I’ve been reading in the newspaper about the war between Ethiopia and Eritrea. There are rumours that a Mig29 plane from Eritrea was captured (?) near Bahardir, a town in the north. It doesn’t seem very clear why this war is happening. The OAU say that Eritrea is the agressor, and so do most Ethiopians, but there may be a not very well hidden agenda of Ethiopia wanting a Red Sea port - at the moment it doesn’t have one, so exports have to go through Eritrea - with all the stuff to do with customs, tax, etc.’

At the end of the first week, we took the participants to the National Museum of Ethiopia. This was the first time any of them had been to this or any other museum. It was also their first experience of

looking closely at many artefacts of Ethiopian culture. For the first hour, we asked them to look at and sketch details of pattern and texture in the various objects in the museum. For the second hour they were asked to draw one particular item in the display. For the third hour they simply continued sketching any of the objects which took their interest.

By this stage in the workshop, we seemed to have more students than we started with - something like 23. It was a very enjoyable and really interesting afternoon at the museum.The kids were very excited and running around at first but soon calmed down and started to examine the displays. They worked hard on their drawings and showed great interest in the collections - from portraits of historical figures such as Tewodros and Haile Selassie, to examples of wooden ploughs, musical instruments, pottery, religious paintings, a large bronze Lion of Judah, a contemporary photograph of an Ethiopian woman baring her breasts, traditional costumes, guns, swords, the famous skeleton of Lucy, carved angels, the Virgin Mary with one of her tits out, poking her finger into the eye of a blind boy so that her milk might restore his sight, comic-strip stories from the Bible, big eyes, strange body proportions, and so on. A memorable outing for all of us, I think.

The following day, a Sunday, we were given the use of a car and a driver, Josef, so we went out with Enanate, the co-ordinator of the Adugna Dance Group at the Gemini youth centre, to explore a bit of the countryside. We first went to a place where ‘holy water’ was dripping down a large rock face. The guide was a comical old boy who, as he spoke, gestured expressively with a green and white stick. He made us bend our heads under the dripping water so that we would be attended by good fortune. Then we had a great drive via Debre Zeit, up to Nasret in the Rift Valley - wide open scenery, termite mounds, vultures, large crowds of people coming out of church in white dresses with strips of Rastafarian colours around the edges.

Just before Nasret, we came across a young boy herding a few young camels. He let us feel the fineness of their hair - very, very soft - and charged us a small fee to take his photo. We had lunch at Nasret before making our way back to Addis through a heavy rainstorm. A good day. Enanate had enjoyed it, having munched his way through a whole carrier bag full of Khat, the government drug.

For the second week of the workshop participants made a variety of materials - decorative pictures using ‘calligraphy’, the amharic script; painted signboards for shops such as hairdressers, fruit stalls and hardware; poster designs for the forthcoming performance of “Firebird” by the Adugna Dance co.; pictures based on the young peoples’ own experiences of life on the street.

It was beginning to feel pretty unhealthy in the container, all of us in such a small space for most of the time. After lunch at our usual shack restaurant, Liz vomited again. The standards of hygiene here are generally abominable, almost worse than India, and it was becoming quite hard for people to keep going in these circumstances. Our interpreter looked really ill today and thinks he’s got ‘flu, whatever that means. Several of the kids complained of headaches and spent some time slumped over the desk. Progress was fairly slow but the young people soldiered on, poor things. It really was a wretched place and very different from our previous workshop in Ethiopia, when we worked in a relatively hygienic training centre.

One evening during the week I treated myself to a haircut. The barber used electric hair clippers as a

thunder and lightning storm erupted above his little shop. He’d got half way through my haircut when the power went off, leaving me a bit lopsided - but fortunately the power came back on after a short while. Later that evening, I discovered that the war with Eritrea had intensified, so my plan to get a flight north to visit the churches at Gondar and Lalibela had to be abandoned.

Things improved as the week went on and it was encouraging to see the participants’ materials taking shape. They made some good designs and a few quite moving drawings about life on the street, including one which showed a young person hanging from a tree with a noose round his neck. It is profoundly sad to learn about their lives. The work continued to its conclusion at the end of the week, always with a good ‘atmosphere’ in our container. The kids were generally proud of what they had achieved and I guess it had been an interesting interval for them. We celebrated by having a meal of spaghetti and Ethiopian wine. Spaghetti is quite common here, part of the Italian legacy along with the Roma Bar, the Pisa Bar, the Leonardo Stationery Shop and the local version of capuccino.

MISCELLANY

The Queen of Sheba - Ethiopians say she came from Ethiopia, Saudis say she came from Saudi Arabia and Yemenis say she came from Yemen. The Ethiopian version is that her capital was, around 1000 BC, in Axum, in the north of Ethiopia, not far from Eritrea. She travelled to Jerusalem to visit King Solomon, they got on well, she went back to Ethiopia and 9 months later gave birth to a baby boy who she called Menelik. He was the founder of the Solomonic dynasty of which Haile Selassie claimed to be the 225th emperor. When Menelik grew up, he went to visit his father in Jerusalem. When he returned to Ethiopia, a year or so later, he and a few of his pals stole the Ark of the Covenant and took it back to Axum. The Ark is a box in which the tablets or slabs of stone on which the Covenant between God and Moses (the ten commandments, etc.) was carved. Nobody has seen the Ark for a few thousand years and there has been a lot of speculation concerning its whereabouts, books written, conspiracy theories developed, films made...It is generally thought to still be in a chapel in Axum, whose roof started leaking a few years ago, but there are various other contending locations, even one in Warwickshire!

The Falashas - these are Jewish people who have traditionally lived south of Axum and just to the north of Lake Tana. Throughout their history, they have been persecuted, like many other Jews, by their neighbours, in this case the Amhara who are, of course, Christian. Apparently the Falasha carry out religious ceremonies and follow observances that haven’t changed for 3000 years. Their existence became more widely known since the time of the 1985 famine under Mengistu, as the Israeli government invited many of them to re-settle in Israel. Something like 120,000 Falashas, half of them born in Ethiopia, today live, often rather miserably, in Israel.

According to an article from June 2012 published in the Middle East Monitor by Dr. Hanan Chehata:

“Poverty is three times higher among Ethiopians than among other Jewish Israelis, and unemployment is twice as high. Ethiopian youngsters are much more likely to drop out of school and are vastly under-represented at the country’s universities. One place they are over-represented is in jail: juvenile delinquency runs four times higher in the community than among Israelis overall.”

I’m not sure about the numbers at all, but I think it is true to say that there are currently an awful lot more Falashas in Israel than in Ethiopia.

The Battle of Adwa - this was an important event in the history of modern Ethiopia. It took place in 1895/6 in the north of the country when the Italians who occupied Eritrea attacked Ethiopia in an attempt to eventually colonise the country. With the help of some strategic Italian cock-ups, the Ethiopian fighters, who came from all parts of the country and from all ethnic groups (unification!), overwhelmed the Italians and won easily, taking, in the process, lots of Italian prisoners. For the time, this was a pretty amazing outcome. Most other countries in Africa had been colonised by European powers and were ruled by them, often in fairly brutal ways (e.g. Congo). It was the first time Blacks had beaten Whites! In fact, Ethiopia was never properly ‘colonised’. (As far as I know there was only one other African country that was not a colony of Europe - that was Liberia.)

Bahru Zewde writes: “The repatriation of the thousands of Italian prisoners captured at Adwa preoccupied the new Italian regime. To achieve this, it even managed to persuade Pope Leo XIII to write a letter to Menelik in May 1896 urging clemency. Menelik responded by making the release of the prisoners dependent on the signing of a peace treaty. ‘In the circumstances’, he wrote back, ‘my duty as king and father of my people dissuades me from sacrificing the sole guarantee of peace that I have with me’. At a later time, the Italian fascists under Mussolini occupied Ethiopia from 1936 until 1941, when Addis was liberated with the help of the British.

Haile Selassie - was born in 1892 in Harar, in eastern Ethiopia, and was given the name Tafari Makonnen. He was born in a mud hut, although his father was governor of Harar. When the emperor Menelik II died in 1913, he didn’t have a male heir, so his grandson was appointed emperor. He didn’t last long, though, as Tafari gained power in 1916. By 1928 he had become the undisputed leader of the country, so appointed himself king. Two years later when Menelik’s daughter Zauditu, who had been empress, died Tafari was made emperor, a job he kept until 1974! Lots has been written about him and the good and bad that was one during his reign. I haven’t read much of it, but I would strongly recommend the incredible story of his last years, written by Ryzard Kapuscinski, entitled simply ‘The Emperor’. A couple of extracts give something of the flavour of Kapuscinski’s account:

“He not only never used his ability to read, but he also never wrote anything and never signed anything in his own hand. Though he ruled for half a century, not even those closest to him knew what his signature looked like. During the Emperor’s hours of official functions, the Minister of the Pen always stood at hand and took down all the Emperor’s orders and instructions...His Majesty spoke very softly, barely moving his lips. The Minister of the Pen, standing half a step from the throne, had to bend his ear close to the Imperial lips in order to hear and write down the Imperial decisions.”

“His Majesty would take his place on the throne, and when he had seated himself I would slide a pillow under his feet. This had to be done like lightning so as not to leave Our Distinguished Monarch’s legs

hanging in the air for even a moment. We all know that His Highness was of small stature. At the same time, the dignity of the Imperial Office required that he be elevated above his subjects, even in a physical sense. Thus the Imperial thrones had long legs and high seats, especially those left by Emperor Menelik, an

exceptionally tall man. Therefore a contradiction arose between the necessity of a high throne and the

figure of His Venerable Majesty, a contradiction most sensitive and troublesome precisely in the region of the legs, since it is difficult to imagine that an appropriate dignity can be maintained by a person whose legs are dangling in the air like those of a small child. The pillow solved this delicate and all-important

conundrum. I was His Most Virtuous Highness’s pillow bearer for twenty six years. I accompanied His

Majesty on travels all around the world - His Majesty could not go anywhere without me....In my

storeroom I had fifty two pillows of various sizes, thicknesses, materials and colours. I personally monitored their storage, constantly, so that fleas - the plague of our country - would not breed there, since the

consequences of any such oversight could lead to a very unpleasant scandal”.

One of the leaders of the partisans in the war against Mussolini, Tekele Wolda Hawariat, didn’t get on very well with Haile Selassie - “He refused to accept graciously tendered gifts, refused special privileges, never showed any inclination to corruption. His Charitable Majesty had him imprisoned for many years, and then cut his head off”. Finally, Haile Selassie was deposed in the coup led by Mengistu - some accounts even have it that it was Mengistu who killed him, by suffocating him with a pillow. The rest is history.

Ras, in Amharic, means ‘king’ or ‘head’. Tafari was Haile Selassie’s given name. It means ‘one who is to be respected or feared’. The Rastafarians of Jamaica worship Haile Selassie as their leader. Again, there are other places where one can learn about Rastafari. Red, Green and Gold are the colours of the Ethiopian flag. The first Rastafarian settled in Shashamane, Ethiopia, dope-smoking capital of the world, in 1965, having hitch-hiked from England. In April 1966, Haile Selassie visited Jamaica, to be welcomed at Kingston airport by 100,000 Rastafari ‘smoking a great deal of cannabis and playing drums’ (Wikipedia). Bob Marley’s wife Rita said that she saw stigmata appear on his person and converted to the Rastafari faith. Someone I met in Ethiopia told me that before his arrival in Jamaica there had been a long drought and that when Haile Selassie’s plane touched down, it started to pour with rain, thus convincing the reception commitee of his divinity. I don’t know much about Rastafari but some of their beliefs seem a bit odd e.g. that smoking marijuana is a cure for asthma.

Music in Ethiopia is wonderfully diverse. I heard a certain amount live on my trips - some traditional, some westernised ‘hotel’ music. As ethnomusicologist Cynthia Tse Kimberlin notes in the book “Musics of Many Cultures”, Balint Sarosi points out that Ethiopia’s location, geographically, makes it susceptible to many musical influences. “Ethiopia is located, so to speak, at the very crossing point of the most important musical tendencies. Looking at the map, we can already gather that in this area the North African arabesque chromatic style had to meet the more simple pentatonic...musical world of Central Africa. Indeed, the musical material reveals the fruitful conjunction of the two different musical styles”. And Cynthia adds “There is no one kind of music that could truly represent the entire country, for how could a country with so many ethnic groups and languages, isolated by geographical, political and cultural boundaries produce homogeneous music?” As a foreign ignoramus, I do, however, think that one can hear a common sound or voice in most of the Ethiopian music I have heard. One of the best known Ethiopian musicians is the singer Gigi, who happens to be married to the very interesting American dub/bass musician/producer Bill Laswell. Gigi’s music is well worth listening to. Alf also introduced me to Dub Colossus, who are great and usually perform a bit of the shoulder dancing that is characteristic of Ethiopia. It’s a weird one but seems to turn some people on. Some of the traditional instruments are interesting, too. “The krar is a five- or six-stringed lyre”, writes Cynthia, “consisting ofd two upright pillars joined by a crossbar at the top”. The masinqo is another strange-looking instrument. It is the only Ethiopian bowed instrument. It’s a bit like a violin with only one string and sounds great (in the right hands). The sounbox is usually diamond-shaped.

Most of the traditional visual art of Ethiopia, as in other countries, takes religious themes as its subject matter. The best examples are in churches in Gondar, which I was unable to visit because of the short war with Eritrea. Fortunately, it is easy enough to see some of these in reproduction. There is also a strong tradition of illuminated religious texts which clearly relate to the imagery used Christian Orthodox books and bibles from other cultures. One of my favourite images is the painting that decorates the ceiling of the church of Debre Berhan Selassie. It shows several rows of archangels with big eyes which are believed by some to follow people as they come into the church. This way of depicting the face has become widespread in Ethiopian art - as in the picture of the krar player.

The traditional texts are written in the liturgical language called Ge’ez, a relative of Amharic. There are, of course, many different languages in Ethiopia, particularly in the south, which is something of an ethnographic hot-spot, with its multitude of ethnic groups. On the plane home, I met an Englishman man who had, with his wife and two children, been living for two years in a remote village somewhere in the south. I wondered why anyone in their right mind might do such a thing. He told me that he had worked as a bank clerk in Bromley, Kent for several years since leaving school. Latterly he started to question the way he was spending his time and decided to change his life into a more meaningful one. He was in Ethiopia on behalf of a Christian missionary organisation. He was working, with Ethiopian colleagues, on a dying language which was spoken by less than 100 people, and had never been written down. He and his team were in the process of creating an alphabet for the doomed language. They had been working on it for two years and had reached, in our terms, about g or h. It was a race against time, as most of the people who spoke the language were very old. I received newsletters from him for a few years but never really read them, rather akin to the way I treat the publications of the Jehovah’s Witnesses which are regularly delivered to me by a window cleaner from Leiston and one or other of his misguided cohorts.

Thursday, 1 January 2015

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)